هُوَ الَّذِيٓ أَرۡسَلَ رَسُولَهُۥ بِالۡهُدَىٰ وَدِينِ الۡحَقِّ لِيُظۡهِرَهُۥ عَلَى الدِّينِ كُلِّهِۦۚ وَكَفَىٰ بِاللَّهِ شَهِيدٗا

“He it is Who has sent His Messenger, with guidance and the Religion of Truth, that He may make it prevail over all other religions. And sufficient is Allah as a Witness” (48:29).

Following the advent of the Holy Prophet Muhammad (peace and blessings of Allah be upon him), Islam spread rapidly throughout the known world, from the Pacific to the Atlantic. Undoubtedly, the message was universal, and Allah the Almighty promised to spread it to the farthest corners of the world. To the far east lies a country that awaited many centuries for the fulfillment of this Divine promise – Japan.

Islam

Despite Islam having reached mainland Eastern Asia (China and Korea) by the seventh century, it was not able to reach Japan until the 19th century. This was due to two major factors. Firstly, the Portuguese and Dutch brought Christianity to Japan in the 15th century and started aggressively promoting Christianity and monopolizing trade, which sparked a conspiracy that threatened Japan’s leadership. Secondly, Japan implemented an isolation policy from 1603 to 1867, strictly limiting travel for Japanese citizens and restricting foreigners. As a result, Islam only arrived in Japan at the end of the 19th century.

Islam was introduced in Japan at the end of Japan’s isolation (1603–1867) in the period of Japanese history known as the Meiji Restoration. During this time, Japan allied with the Ottoman Empire due to their mutual disassociation with the Western powers. The first official contact between Japan and the Islamic world occurred at the end of the Tokugawa shogunate, and relations gained momentum during the reign of Emperor Meiji, which began in 1868. One of the first Muslim states Japan reached out to was the Ottoman Empire. In 1878, a Japanese delegation anchored in Istanbul while going for a training mission, and then in 1881, another visit happened to advance bilateral talks to sign the “Japan-Ottoman Friendship Agreement.” In 1887, Prince Komatsu Akihito of Japan visited Istanbul. The Sultan gave them lots of Ottoman metals as gratitude, and in return, the Sultan received the Order of the Chrysanthemum (the Highest order in Japan). In response, Sultan Abdul Hamid II sent a delegation to Japan in 1889 aboard the Ertuğrul Battleship.

The Ertuğrul arrived in the Japanese city of Yokohama in June 1890, where the fleet commander, Osman Pasha, presented Sultan Abdul Hamid II’s letter and gifts to the Japanese emperor. The delegation stayed in Japan for three months before embarking on their return journey. Unfortunately, the Ertuğrul encountered a typhoon off the coast of Kushimoto, leading to the tragic sinking of the ship and the loss of 581 officers, including the Sultan’s brother. The survivors were brought back to Istanbul on two Japanese warships: Hiei and Kongo (Bulut; Al Samarrai; Kronoloji).

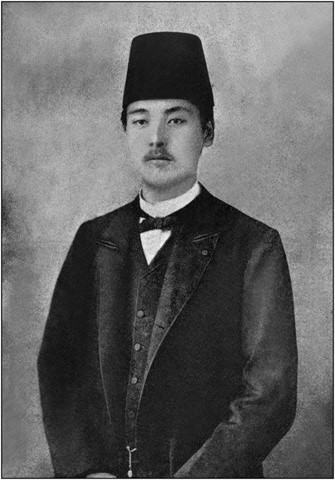

On board the ships carrying the survivors was a young Japanese journalist, Shotaro Noda, who had helped raise funds for the victims’ families. Upon arriving in Istanbul, Noda met Sultan Abdul Hamid II, who invited him to stay and teach Japanese to Ottoman officers. During his time in Istanbul, Noda embraced Islam and changed his name to Abdul Haleem in 1891. His conversion is considered the first known case of a Japanese individual converting to Islam (Al Samarrai; Bulut).

After the Russo-Japanese War in 1905, news spread through the press that the Japanese showed interest in Islam as well as the Muslim world. Japan’s victory over Russia, which had a large Muslim population, contributed to this interest. Almost 5000 Tartar Muslims Captives were accommodated in various detention camps in Japan. The Japanese segregated them from the Russians, and for them, the first mosque was built in Japan, although it was a temporary mosque. In 1906, there were rumors that a conference of different religions would be held in Tokyo and that the emperor was interested in converting to Islam, which sparked interest among Muslims about Japan. However, it’s unclear if this conference ever actually took place, and many believe it was just propaganda. This was likely part of Japan’s strategy to gain support from Muslims, especially in China, as Japan looked to expand its influence in Asia after its victory over Russia in the Russo-Japanese War. Japan’s new status as a world power made this effort part of a larger political move to build ties with Muslims and strengthen its position in the region (Al Samarrai; fountainmagazine; Bodde).

In 1909, the first structured efforts for the propagation of Islam were started by an Egyptian Muslim named Ahmad Fadly (fountainmagazine).

In the aftermath of Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War, Tatar Muslim immigrants flocked to Japan to escape communist Russian rule. Most of them settled in Tokyo, Nagoya, and Kobe. Due to the abundance of Indian Muslim Traders in Kobe, the first permanent mosque in Japan was built there in 1935. A few years later, in 1938, a mosque was built in Tokyo (which was later demolished due to damage, and a new one was built in its place). Another mosque was built in Nagoya, but it was destroyed in World War 2 (Al Samarrai; fountainmagazine).

In the Second World War, Japan sided with the Axis powers and continued the expansion of its empire into the Asian mainland as well as in the Pacific, which resulted in a large influx of Muslims from conquered territories now seeing themselves under Japanese rule. During the war, many Japanese soldiers embraced Islam after encountering Muslims in China, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines. After Japan lost the war, all military forces were recalled to Japan, which consequently brought all these new Japanese Muslims to the mainland as well.

Furthermore, during World War II, interest in Islam increased due to the government setting up organizations and research centers on Islam. Over 100 books and journals on Islam were published. Muslims didn’t run these, and their purpose was to educate the military on Islam to be able to govern the large muslim communities in areas such as China and Southeast Asia. After the war, these organizations and research centers disappeared. As a result, it is unclear whether many of these conversions to Islam were authentic or for war purposes (Al Samarrai; fountainmagazine).

From the end of the 1950s to the 1960s, there was a high influx of foreign students coming to Japan for education. Foreign students from countries like Turkey, Pakistan, Indonesia, and various parts of the Arab world formed various Muslim Student Associations, which contributed significantly to the propagation of Islam (Al Samarrai).

In 1970, King Faisal bin Abdul Aziz of Saudi Arabia visited Japan, meeting with students and discussing the propagation of Islam. After these discussions, King Faisal was persuaded to send university professors to assist in propagation efforts, provide funds for various institutes, and support the establishment of Islam in Japan. This resulted in the establishment of “The Islamic Center-Japan,” whose objective was to publish Islamic literature, support Muslims around Japan, set up cultural events, Hajj missions, and establish the Arabic Islamic Institute in Tokyo. This was but one of the various Muslim organizations that existed during this time for the propagation of Islam, with the earliest being in 1953 (Al Samarra; fountainmagazine).

Between 1920 and 1970, five attempts at the translation of the Quran into Japanese were made, but the competence of these attempts and the knowledge of the Arabic language of the writers isn’t verified. In 1972, a proper copy was published by Umar Ryochi Mita after having dedicated 13 years of his life to this task (fountainmagazine).

Another wave of interest in Islam and the Muslim world was triggered by the so-called ‘oil shock’ of 1973. Recognizing the growing economic significance of oil-rich countries, Japanese media began to focus more on the Arab world and Islam. This exposure introduced many Japanese people, who had previously known little about Islam, to images of the pilgrimage to Mecca, as well as the sounds of the call to prayer and Qur’anic recitations (fountainmagazine).

In 1977, a mosque was established in Osaka by a native Japanese Muslim (fountainmagazine).

The greatest development in the history of Islam in Japan occurred in the mid-1980s when a mass influx of Muslim immigrants arrived from Indonesia, Pakistan, Bangladesh, India, Sri Lanka, Iran, Afghanistan, African countries, Turkey, and the Arab world. Many of these immigrants married Japanese women, passing Islam onto their wives and children. They also built mosques, prayer halls, halal food restaurants, and halal product shops. In 1986, the Tokyo Mosque was demolished and rebuilt, completing its construction in 2000 (Al Samarrai).

Ahmadiyyat

As interest grew in Islam, the Promised Messiah (peace be upon him) also learned of this. He was eager to convey true Islam. He said:

“The Japanese are looking for an excellent religion. Who will take their rotten and worn-out provision? A few men should be prepared for this work from among this Jama‘at who are competent and courageous and possess the substance of eloquence”

(Malfuzat, vol 7, p. 333, August 13, 1905).

He said on another occasion, “If I were commanded by God, I would leave this very day without even learning the language”

(Malfuzat, vol 7, p. 243, June 26, 1905).

Additionally, the Promised Messiah (peace be upon him), expressed his desire to publish a brief book in Japanese that would summarize the fundamental principles of Islam, aimed at conveying the message of Islam to the people of Japan, as he said

“I have come to know that the Japanese people are showing interest in Islam, so there should be such a comprehensive book in which the truth of Islam is fully recorded, as if it were a complete picture of Islam. In the same way that when a person describes someone thoroughly, he provides a picture of the person from head to toe, in the same way the excellences of Islam should be set forth in this book. All aspects of its teachings should be discussed, and its fruits and results should also be shown. The moral part should be separate, and it should be compared with other religions.”

(Malfuzat, vol 7, p. 353, September 16, 1905)

And:

“A book should be written for the Japanese. An eloquent Japanese individual should be paid 1,000 rupees to translate it, and then 10,000 copies should be printed and published in Japan.”

(Malfuzat, vol 8, p. XXXV)

After the Promised Messiah (peace be upon him) expressed his desire to spread Islam in Japan, Hazrat Mufti Muhammad Sadiq sahib (may Allah be pleased with him) immediately began writing letters to the Japanese people (“Dawn of a New Sun: History of Islam-Ahmadiyya in Japan”).

The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community first established its presence in Japan in 1935, under the guidance of the Second Khalifa, Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmad (may Allah be pleased with him). This outreach to Japan was part of the Tehrik-e-Jadid scheme, a broader campaign established for the spreading of Islamic teachings through Ahmadiyya missions worldwide. Regarding Tehrik-e-Jadid and Japan, Hazrat Musleh Maud (may Allah be pleased with him) has stated:

“The first task of Tehrik-e-Jadid is to establish at least one person in each country of the world who can firmly grip the standard of Islam and wave the flag high in the air. In Japan, there should not be a Hindustani waving the flag of Islam; rather, there should be some native Japanese who firmly uphold the standard of Islam.”

(Friday Sermon, December 1, 1939)

Missionary work began on June 4th, 1935, in the City of Kobe with the arrival of Sufi Abdul Qadeer Niaz. He made it a priority to start learning Japanese and dedicated himself to this task. (“Dawn of a New Sun: History of Islam-Ahmadiyya in Japan”; Ahmad, Jalees) He was later joined by Hafiz Abdul Ghafoor. Before departing, Hazrat Musleh Maud (may Allah be pleased with him) wrote to him, reminding him of his purpose for traveling to Japan. Huzoor (may Allah be pleased with him) said that he would face many difficulties, such as financial troubles. He advised him to always remain steadfast and to continuously seek God’s help and have firm faith in him. He also advised him to keep up to date with the current affairs and read their newspapers daily. (Tarikh-e-Ahmadiyyat, vol 8, pp 219-220) Once arriving in Japan, Hafiz Abdul Ghafoor Sahib learned Japanese from Abdul Qadeer Sahib (Ahmad, Jalees). However, their missionary activities came to an end with the outbreak of World War II, which forced both men to leave in 1941 (“Dawn of a New Sun: History of Islam-Ahmadiyya in Japan”).

In the last days of World War II, Hazrat Musleh Maud (may Allah be pleased with him) had a vision about Japan:

“The Japanese nation, which is currently in a completely lifeless state, will have a desire for Ahmadiyyat instilled in its heart by Allah Almighty. Gradually, it will regain strength and power and will respond to my call just as the birds responded to the call of Prophet Abraham (peace be upon him).”

(Friday Sermon, March 18, 2011)

In 1945, two atomic bombs were dropped on Japan in the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Hazrat Musleh Maud (may Allah be pleased with him) spoke about this incident and quoted the revelation of the Promised Messiah (as): “These cities will cause people to weep” (Tadhkirah [English], p. 981; Khutbat-e-Mahmud, vol. 26, pp. 314-315). Hazrat Musleh Maud (may Allah be pleased with him) further explained:

“As far as humanity is concerned, destruction of this kind cannot be declared lawful. There had always been wars and enmities, but despite those enmities and wars, there were some limits fixed, which were never violated. However, there is no limit now… Although our voice may be [considered] of no value, it is our religious and moral duty to announce to the world that we do not consider such bloodshed as lawful, notwithstanding if our announcement makes certain governments pleased or displeased.”

(Friday Sermon, August 10, 1945 – Khutbat-e-Mahmud, vol. 26, pp. 314-315)

At the 1951 San Francisco Peace Conference, Pakistan was the only major country invited from South Asia. A Pakistani delegation, led by Foreign Minister Hazrat Sir Zafarullah Khan (may Allah be pleased with him), passionately argued in favor of treating Japan with respect. Sir Zafarullah Khan (may Allah be pleased with him) made a historical speech, noting that, “The peace with Japan should be premised on justice and reconciliation, not on vengeance and oppression” (“Brief History of Pakistan-Japan Bilateral Relations”). He also mentioned that due to the heavy sanctions placed on Germany after World War I, Nazism rose in Germany, and as such Japan should not be treated in the same manner (“Dawn of a New Sun: History of Islam-Ahmadiyya in Japan”).

Hazrat Musleh Maud (may Allah be pleased with him) has stated:

“Japan is such an extraordinary nation: if we can establish a mission there, then the voice of Ahmadiyyat will echo throughout East Asia.”

(Friday Sermon, November 19, 1954)

In 1968, while touring Japan, Sahibzada Mirza Mubarak Ahmad Sahib, who served as Wakil-e-Ala and Wakil-ul-Tabshir Tahrik-e-Jadid, analyzed the feasibility of establishing a permanent mission house. After his assessment, Mirza Mubarak Ahmad returned to Japan and presented his findings to the Jama’at in a speech at the Jalsa Salana in Rabwah. Satisfied with his report, Hazrat Mirza Nasir Ahmad (may Allah have mercy on him), the third Khalifa of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, sent Major Abdul Majeed Sahib as a missionary to Japan. His efforts were met with immediate success as 30 people entered the fold of Islam and Ahmadiyyat. In 1970, Major Abdul Majeed sahib was invited to a religious conference held in Kyoto as a representative for the Ahmadiyya community (“Dawn of a New Sun: History of Islam-Ahmadiyya in Japan”).

The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community’s presence grew stronger when Ataul Mujeeb Rashed sahib began his eight-year missionary service in Japan. He served from 1975 to 1983 and became the first Amir Jama’at of Japan. He could often be found handing out religious flyers at the Hachiko exit of Tokyo’s Shibuya Station (Penn; Dawn of a New Sun: History of Islam-Ahmadiyya in Japan”; Ahmad, Jalees)

Hazrat Khalifatul Masih III (may Allah have mercy on him) had decided that it would be more effective to spread Islam in rural towns instead of the capital cities, due to them already being saturated with other missionary activities. Ataul Mujeeb Rashed Sahib had proposed Nagoya to be the community’s capital in Japan. He explained, “I proposed Nagoya firstly because it was the fourth-largest city in Japan, and secondly because, geographically speaking, it is right in the middle of Japan” (Penn).

The main method of propagation was through literature. Imam Sahib had a small white Toyota with Islamic slogans written in English, Arabic, and Japanese. He attached a speaker to the car and traveled across Japan, handing out literature and making the Japanese people hear the message of the Promised Messiah (peace be upon him). The ‘Toyota in the Service of Islam’ was the focus of great curiosity wherever it passed.

A pivotal moment came in September 1981, when, following the Caliph’s guidance, the community purchased its first mission house in Nagoya — a two-story building that became their new headquarters. This was followed by greater efforts in publications, and led to the introduction of the Jalsa Salana, the Shura system, and the establishment of auxiliary organizations such as Khuddam-ul-Ahmadiyya and Lajna Imaillah in Japan. (Penn; “Dawn of a New Sun: History of Islam-Ahmadiyya in Japan”).

In August 1979, Maghfoor Ahmad Muneeb Sahib joined Ataul Mujeeb Sahib as a missionary of the Jama’at in Japan (Ahmad, Jalees).

In August 1987, Hazrat Khalitatul Masih IV (may Allah have mercy on him) sent Faheem Ahmad Sahib as another missionary to Japan. He enrolled at the Naganuma School (Tokyo School of Language) to learn Japanese. Two years later, in 1989, Ziaullah Mubashar Sahib was also sent to Japan and later appointed as the Amir of Japan until 1998, when he returned to Rabwah. After this period, there were no missionaries in Japan for approximately one to two years (Ahmad, Jalees).

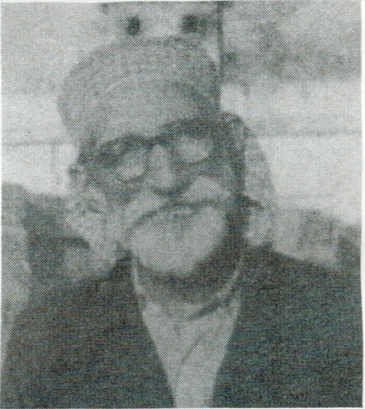

In 1988, after two years of effort, the Holy Quran was translated into Japanese by Muhammad Uwais Kobayashi under the auspices of Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IV (may Allah have mercy on him). He was formerly known as Atsushi Kobayashi and embraced Islam in 1957.

Born into a Shinto family, Kobayashi had developed an interest in Islam while studying Japanese literature at Tokyo University during his 20s. After World War II, the President of Pakistan, General Ayub Khan, visited Japan, and Kobayashi Sahib had the opportunity to meet him and express his interest in Islam. General Sahib advised him to go to Pakistan if he wanted to learn more about Islam. Consequently, Kobayashi Sahib traveled to Pakistan, where he began studying Islam. He was then introduced to Ahmadiyyat by a gentleman and was invited to Rabwah. When the people he was staying with learned of his interest in Rabwah, they told him that demons lived there and would eat him. Since Kobayashi sahib had read about Satan in Islamic literature and demons in Japanese manga comics, he became quite curious. One night, after they fell asleep following the Isha prayer, he left and walked for 5–6 hours to Lahore Station. There, he called the gentleman who picked him up and took him to Rabwah. Kobayashi Sahib later said he did not encounter any demons or Satan there. He also spent a year studying at Jamia Ahmadiyya to learn more about Islam. During this time, he said that in his heart, he had accepted Ahmadiyyat, but not yet officially. He returned to Japan in 1959, where he worked closely with the missionaries who came to Japan. He officially accepted Ahmadiyyat between 1970 and 1975 (Ahmad, Jalees; MKA UK).

1989 proved to be a landmark year for Japanese Ahmadi Muslims. The community celebrated a historic visit by the Fourth Caliph Hazrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad (may Allah have mercy on him). During the visit, he delivered the first Friday Sermon by a Khalifa of the Promised Messiah (peace be upon him) on Japanese soil from Nagoya. Hazrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad (may Allah have mercy on him) praised the morality of the Japanese people and highlighted their truthfulness (“Dawn of a New Sun: History of Islam-Ahmadiyya in Japan”; Ahmad, Anees).

In 2006, Japan was again blessed with the presence of a Khalifa when Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad (may Allah be his Helper) visited Japan for Jalsa Salana Japan. His Friday Sermon made history as the first to be broadcast live from Japan to the entire Ahmadiyya community via MTA. During this trip, he urged the Jamaat to build a mosque. He returned to Japan in 2013 when the construction of the mosque had begun, and again in 2015 for the inauguration of the Bait ul Ahad mosque, the first Ahmadi mosque in all of Eastern Asia (“Dawn of a New Sun: History of Islam-Ahmadiyya in Japan”; Ahmad, Anees).

Islam’s arrival in Japan faced many challenges. Still, due to the blessings of Allah, Islam has now arrived in Japan and is quickly growing, becoming one of the country’s fastest-growing religions. The day is not far when the wishes of the Promised Messiah (peace be upon him) will come true and the Japanese nation will accept Islam in droves, God-Willing.

Bibliography

- Ahmad, Anees. https://fountainmagazine.com/all-issues/1997/issue-18-april-june-1997/islhttps://themuslimtimes.info/2015/03/23/the-history-of-muslims-in-japan-by-anees-ahmad-nadeem-2/am-in-japan.

- Al Samarrai, Salih Mahdi S., Prof. Dr. تاريخ الاسلام فى اليابان – انجليزي. Accessed 7 Nov. 2024.

- Bodde, Derk. “Japan and the Muslims of China.” Far Eastern Survey, vol. 15, no. 20, 1946, pp. 311–13, https://doi.org/10.2307/3021860.

- “Brief History of Pakistan-Japan Bilateral Relations.” Pakistan Embassy Tokyo Japan, https://www.pakistanembassytokyo.com/content/brief-history-pakistan-japan-bilateral-relations. Accessed 10 Nov. 2024.

- Bulut, Mehmet Hasan. “Shotaro Noda: Ottoman Journey Makes Him 1st Japanese Muslim.” Daily Sabah, 1 June 2021, https://www.dailysabah.com/arts/portrait/shotaro-noda-ottoman-journey-makes-him-1st-japanese-muslim.

- “Dawn of a New Sun: History of Islam-Ahmadiyya in Japan.” Islam Ahmadiyya, https://www.alislam.org/video/dawn-of-a-new-sun-history-of-islam-ahmadiyya-in-japan/. Accessed 7 Nov. 2024.

- fountainmagazine.

- https://fountainmagazine.com/all-issues/1997/issue-18-april-june-1997/islam-in-japan.

- Ahmad, Jalees. “Islam’s Journey to Japan Part II Ahmadiyyat in Japan.” Ismael, Jul-Sep 2019 (English).” Issuu, https://issuu.com/waqfenauintl/docs/ismael-jul-sep-2019-en. Accessed 12 Nov. 2024.

- Kronoloji. https://web.archive.org/web/20060111053326/http://www.turkey.jp/tr/kronoloji.htm. Accessed 13 Nov. 2024.

- Penn, Michael. “Japan’s Newest and Largest Mosque Opens Its Doors.” Al Jazeera, 28 Nov. 2015, https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2015/11/28/japans-newest-and-largest-mosque-opens-its-doors.

- MKA UK. “Muqami Interview with First Japanese Ahmadi” – YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pX5wRQ96V-I. Accessed 13 Nov. 2024.